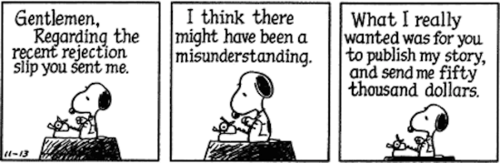

The first story I ever sold was the second-ever story that I sent out to market. I submitted to an anthology invite, was asked for a minor rewrite of the ending (which improved the story), and the editors bought the story–a SFWA qualifying pro sale, in fact.

I had one other story on the market at the time–the first thing I’d ever sent out–and had 8 rejections slips in-hand by the time I made that first sale. I’ve still never sold that first story, having amassed 17 rejections before retiring it from circulation. But I still like it.

I don’t write any of this to brag, but rather in response to a couple of articles I’ve read online in recent days, speaking in defense (and, dare I say ‘praise’?) of rejection.

The first article by Monica Byrne—which I don’t actually take issue with—is her “anti-resume”, an analysis of six-years’ worth of submissions, finding a 3% acceptance rate, which is pretty standard (I’d always heard 2%, so she may actually be ahead of the curve). She submitted to literary journals and magazines, as well as venues more familiar to SF readers (places like Clarkesworld, F&SF, etc,) She has a pretty reasonable view of rejection in the life of a writer, too:

…my anti-resumé reminds me that rejection will always be a part of my career, as in any career, as in anything worth doing. And there are no successful artists I know for whom this isn’t also the case. They love their work. That love buoys them through inevitable and even overwhelming rejection. So I promised myself that, no matter how “The Girl in the Road” was received, I’d start the next book right away. Now I’m 20,000 words in and reminded that just the daily practice of sitting and writing is still the best part. And, like I found that no amount of failure would change that, I hope that no amount of success will, either.

Okay, so no real issue there for me. I went into writing with my eyes open, and I knew there would be a lot of rejection along the way.

Over on English Kills Review, however, Melissa Duclos wrote an article ‘In Defense of Rejection’ in which she cites Monica Byrne as an example of how “Artists need rejection.” Hang on–this is where it gets good:

Every time a writer hears “no”—from a graduate school or a literary journal, an agent or a publisher—she has another opportunity to say “yes.” Does she really want to keep doing this with her life? Yes. Does she really have something interesting to say, that people need to read? Yes. This is not just a matter of endurance, though of course that is part of it.

She makes a number of sweeping generalizations, such as that the rise of self-publishing and the option to skip rejection from editors and publishers all together are “bad news for novels and for writing in general, and even worse for writers.” And again, she says that “Rejection, as maddening as it can be for writers, serves a purpose. Without it, the overall quality of novels on the market has suffered.”

Nowhere in her article, of course, does she substantiate or give any concrete examples to support these claims, nor could she. Taste in literature is completely subjective, after all.

She continues:

A writer who faces rejection—years and years of rejection—will eventually be forced to change, to develop her understanding of form, or her voice, or her handling of characters. She will have to grow in order to break through.

Horseshit.

Don’t misunderstand: I’ve had plenty of rejection. After a spate of quick sales early on, I went two long, cold years with nothing but rejection slips…only to make two pro-level sales within days of one another to break the streak. My most rejected story was rejected 21 times, but then published in a major magazine market and I was immediately contacted out of the blue by an editor requesting a reprint. Did that story suck 21 times, only to be suddenly awesome the 22nd time even though I’d made no changes? Had I somehow forgotten how to write fiction for two years?

Of course not.

Rejection is simply a sign you haven’t appealed to a specific editor’s taste, or they don’t feel like they can sell your work to their publishing board or to their readership. And that’s what this is about–taste making and economics.

Which is A) why you shouldn’t take rejection too seriously/hard, and B) why it’s preposterous to claim that rejection is somehow good or necessary for a writer or their development as an artist. It’s just English Lit Department romanticism about the “tortured artist” that perpetuates this myth.

[pullquote align=”right” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]You don’t need rejection. It’s something you ignore and then carry on writing.[/pullquote]

When Duclos asks whether writers will “choose to be artists striving to make a living, or salespeople, in the business of peddling words?” her misunderstanding of publishing is clear, as is where her sympathies lie: with the romanticized idea of the ‘starving artist.’ This means she’s missed one of the first (and key) points that Byrne made in her article: a desire to make a living from her art.

Artistic idealism is great, but fails to sustain the necessities of life unless coupled with a pay cheque from somewhere. Shakespeare knew this. So did Charles Dickens and Mark Twain. They created great art…which they knew would sell.

You often hear editors say a story or novel wasn’t right for them but then it sells elsewhere. Was there a flaw in the story, or did it just not suit the market? Those are different things. To suggest that rejection will teach something… Will it teach a general lesson, or will it just teach you how best to suit your writing to a specific market. This is the post hoc ergo proper hoc fallacy.

Mind you, there’s nothing wrong with trying to write to suit a specific market. I’d like to be published in ASIMOV’S and am working on stories that I think might appeal to Shelia Williams, and by extension her readership. To date, I’ve had some very nice, encouraging rejections from Shelia. But if she rejects my stories does that mean they won’t sell anywhere? That they’re worthless? That I’m worthless?

Of course not. She rejected that story that was rejected 21 times, and it still sold and sold well when it eventually went.

Besides, how much can you really learn from generic rejection slips? Even personalized rejections rarely have more than a cursory explanation, usually of the “it didn’t work for me”, “didn’t fit my needs”, etc. if an editor takes real time to tell you what needs fixing they are usually offering to buy it (or at least take another look at it) if you make that change.

I keep reminding myself of advice I’ve heard from people like Robert J. Sawyer, Nancy Kress, David Farland, and Kevin J. Anderson: persistence pays off. If you stick with this writing thing, if you love and keep at it, after most others have given up and fallen by the wayside you’ll find success.

It’s said that if you get shit on by a bird it’s good luck. I’m pretty sure that’s just something that people who get shit on by birds tell themselves to make themselves feel better. Saying “rejection is good for you” is nothing different. It’s rejection as the hair shirt of literary practice: a self-mortification.[pullquote align=”left” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]Saying “rejection is good for you” is nothing different. It’s rejection as the hair shirt of literary practice: a self-mortification.[/pullquote]

I always believed that rejection was unavoidable and necessary…but now I don’t know. The rise of self-publishing has meant that even if no editor feels a story works in their magazine or on their website, an author can release it to the world and see what the real arbiter of taste—the reading public—thinks. Look at (admittedly outlier successes) like The Martian, a book that no traditional publisher would publish for a host of reasons. I read it—it was a lot of fun, and a huge success book in print and on film.

Is there also a lot of self-published crap? Yes, of course. 90% of everything is crap, including from traditional publishing venues.

All this smacks to me of snobbery, the defense of some kind of platonic ideal of what it means to write and receive rejection and praise. Shakespeare, Dickens, and Mark Twain all wrote for money and for popular audiences. Those who wrote for some kind of elite audience are forgotten or remembered only in academic circles, where someone needs to find a thesis topic.

Forgotten authors make for good ones.

– S.

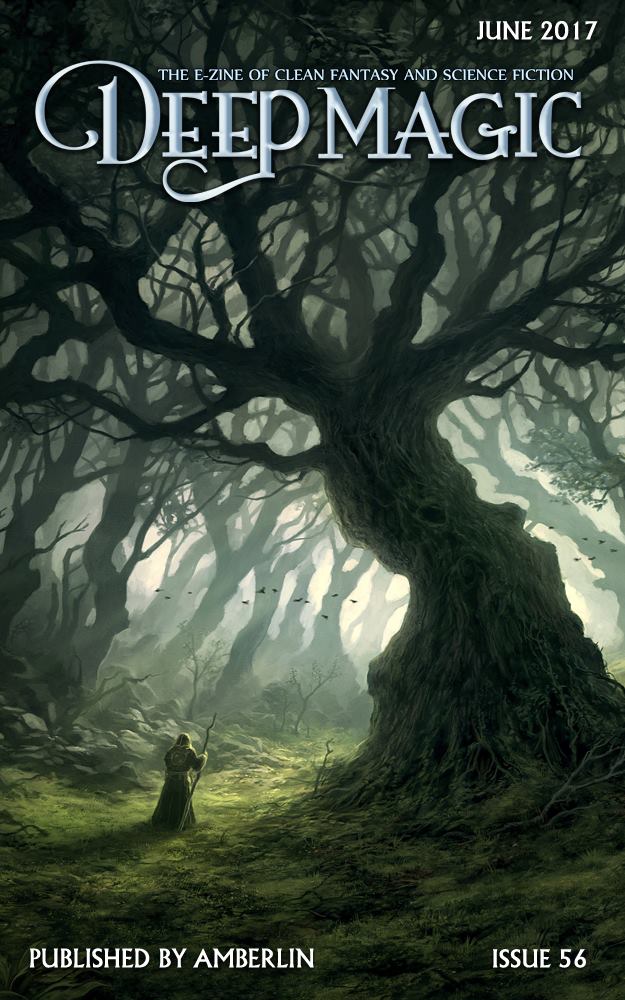

The June 2017 issue of Deep Magic–which includes “The Waxing Disquiet” by Tony Pi and me–is available now! Here’s the epic table of contents for Deep Magic’s 1-year anniversary issue!

The June 2017 issue of Deep Magic–which includes “The Waxing Disquiet” by Tony Pi and me–is available now! Here’s the epic table of contents for Deep Magic’s 1-year anniversary issue!